Raising Awareness about the Positive Influences of Strength and Conditioning Coaches

by Dr. Andrew D. Gillham, PhD, CSCS,*D

NSCA Coach

September 2018

Vol 5, Issue 2

If the strength and conditioning field largely keeps to itself, or the knowledge base is not seen to transcend the training facility, it seems reasonable to think that this will present a problem for strength and conditioning coaches. This article examines some actions strength and conditioning coaches can take to increase the awareness of the good work they do on a daily basis.

There is no debate that the field of strength and conditioning has grown tremendously. How much growth and in what areas depends on who is asked, but the growth is clear and substantial (16,25). The knowledge base of strength and conditioning has grown to such a level that it can be difficult to keep up on what is current, even for those in the field (25). An open question though is how much other sport professionals know about strength and conditioning (19).

If the strength and conditioning field largely keeps to itself, or the knowledge base is not seen to transcend the training facility, it seems reasonable to think that this will present a problem for strength and conditioning coaches. For example, if a faculty member’s first exposure to strength and conditioning was 10 years earlier, and that strength and conditioning coach just yelled at athletes and blew a whistle, that faculty member may not know or understand that student-athletes often confide in the strength and conditioning coach. An additional example pertinent to faculty members can be seen by scrolling through the “Strength Scoop” section of FootballScoop.com.

“If the strength and conditioning field largely keeps to itself, or the knowledge base is not seen to transcend the training facility, it seems reasonable to think that this will present a problem for strength and conditioning coaches.”

Tweet this quote

There are multiple schools looking for volunteer interns at any given point during the year. This shows a need, which is great for the field of strength and conditioning; however, it also says the positions are not valuable enough to pay someone to do it. This particular problem may be seen in budget and staffing discussions with administrators (e.g., why would you need another graduate assistant or full-time position when you can get an intern for free?) or in a general feeling of being stereotyped as a “meathead” and thus, the belief that all strength and conditioning coaches are equal. The purpose of this article is to examine some possible actions strength and conditioning coaches can take to increase the awareness of the good work strength and conditioning coaches do on a daily basis.

Descriptors of a Strength and Conditioning Coach

While much has been written about the educational background of strength and conditioning coaches, there is a significant gap between the education requirements and the necessary skills for success (14). There are at least three consistent themes across the literature: 1) academic course preparation for strength and conditioning coaches is based primarily on the principles of human biology (e.g., biomechanics, exercise physiology, exercise technique, program design), 2) safely training athletes is above all other tasks for a strength and conditioning coach, and 3) the soft skills of coaching (e.g., communication, leadership, interpersonal skills) are typically left as on-the-job training that individual strength and conditioning coaches must develop in order to be successful (16,24,26,31). Other authors have offered suggestions for how to change the training of strength and conditioning coaches, however, a more detailed description of those options will not be presented in this article (19,26,30).

Strength and conditioning coaches have reported the biggest keys to their successes were building trust with their athletes, a willingness to be flexible with workouts, and motivating athletes

(34). All of that combines to leave a significant gap in the career development of strength and conditioning coaches. For example, consider when novice strength and conditioning coaches are included in the various aspects of program design, exercise technique supervision, budget considerations, or meetings with sport coaches. All of those are significant tasks within the job of a strength and conditioning coach (20). It is unclear though how many, and to what extent, novice strength and conditioning coaches are trained in all of the skills needed to be successful in those job tasks before entering the field of strength and conditioning.

“It is unclear though how many, and to what extent, novice strength and conditioning coaches are trained in all of the skills needed to be successful in [important] job tasks before entering the field of strength and conditioning.”

Tweet this quote

Sport coaches and athletic trainers are the professionals that strength and conditioning coaches often work with the closest (36). It seems that every strength and conditioning coach has a story of a meddlesome sport coach or an overly cautious and rigid athletic trainer, some of which have even made it into academic journals (10). Those stories are far from ideal and working to minimize those problems is certainly valuable. Given those issues, the question is: if the strength and conditioning coach is not even seen as an expert by those he or she works most closely with, how will others (e.g., faculty members, athletic administrators) view the strength and conditioning coach as an expert?

Faculty

Campus-wide, faculty members may have an antagonistic view of sports in general due to beliefs about the balance, or imbalance, between academics and athletics and the associated ramifications (e.g., missed classes, not enough time in a day for student-athletes to fully devote themselves to both pursuits, overhearing athletes discussing the difficulty of completing workouts). There are reports of faculty members believing intercollegiate sports are fundamentally incongruous to the mission of higher education (22). This problem is certainly not lessened as a result of scandalous behaviors within athletic departments (22). Additionally, the media has recently reported on strength and conditioning coaches showing problematic behaviors: a heated exchange between a strength and conditioning coach and an official during a football game, being seen as overly intense and attention seeking, and reports of rhabdomyolysis in athletes (1,6,37). Ultimately, to not be lumped into these negative stereotypes, the individual strength and conditioning coach must do something positive to counteract or otherwise set themselves apart from the problematic examples that exist.

While those instances are not widespread or representative of the field as a whole, they certainly do leave a black mark on the image of strength and conditioning coaches and that negativity may need to be overcome. For exercise science faculty, a concern may be that academic journal articles show that training and certification for strength and conditioning coaches does not necessarily lead to research-based training practices by strength and conditioning coaches (18,19). This is especially problematic in that it means some strength and conditioning coaches are training athletes in ways that may put the athletes at risk.

Beyond that, it means the faculty has some degree of doubt that strength and conditioning coaches know what they are doing. This is something that a strength and conditioning coach must overcome for the faculty to place trust in a strength and conditioning coach and believe that they are a truly competent expert adding to the lives of the student-athletes. Establishing and maintaining positive relationships between faculty members and strength and conditioning coaches is important for at least three reasons. First, faculty members are those that are training the next round of strength and conditioning students. If faculty members were to discourage students from pursuing strength and conditioning, that would create widespread problems. Second, faculty members are often in governance roles on campus that can set priorities and policies for the campus (22). As the race for bigger and better facilities within athletic departments continues to escalate, having more faculty members supportive of athletics across campus can only be seen as beneficial (20). Finally, as faculty members seek to secure funding to conduct their research projects, strength and conditioning coaches could receive some of those financial benefits in terms of direct funding or through equipment purchases.

In order to address this issue with faculty members, strength and conditioning coaches must first be aware of the problem. From a wide-angle view, strength and conditioning coaches should want to root out any unsafe coaching practices and remove them from the field. When best practices and guidelines are published they need to be followed. A detailed coaching assessment rubric could be developed based on the standards and guidelines from the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) and individual strength and conditioning coaches as well as whole strength and conditioning staffs could be assessed on their compliance with the standards (31). This would fall within the area of evaluation, which will be addressed in more detail later in this article.

At nearly every collegiate campus in the United States, faculty are responsible for creating scholarly work. The specific definitions of “scholarly work” will vary across institutions, but the general point is that the faculty member needs to be publishing papers and giving academic presentations. This may be the single best way for a strength and conditioning coach to help raise awareness of strength and conditioning with faculty members. Strength and conditioning coaches have tremendous access to the student-athletes and those same student-athletes are who faculty members are frequently trying to recruit as participants in a study. A good word from a strength and conditioning coach on the value of research may help participant recruitment, thereby making the job of a faculty member easier. Some instances may present opportunities for strength and conditioning coaches to be more helpful by yielding a few minutes of training time from a session for athletes to participate in a research project. As simple as it sounds, this may be all it takes to turn a contentious relationship into a collaborative one (11). The collaboration could continue further with co-authorship or co-presenting on the final outputs from the research project (11). These final outputs may also benefit the strength and conditioning coach by qualifying for continuing education credits toward recertification and by refining and improving a the strength and conditioning coach’s skill set. For example, a strength and conditioning coach may want to know more about the benefits of imagery training for athletes after reading an article in Strength and Conditioning Journal. Partnering with a faculty member to conduct a study on imagery with the athletes at the strength and conditioning coach’s school may present an opportunity to improve athlete and coach performance while getting firsthand experience with a topical area the strength and conditioning coach had little exposure to prior to the study.

There are other options for the strength and conditioning coach’s collegiality to be displayed. Not all campuses offer free tickets to sporting events for faculty members and the strength and conditioning coach may have access to offer tickets that otherwise might go unused. Simply reaching out to the exercise science department faculty members to gauge interest in any of the upcoming competitions is an easy way to jump-start collaboration. Another option to show mutual respect is through offering a strength and conditioning logo shirt to a faculty member. That may sound unusual, but the athletic department and staff members usually get substantially more school logo clothing items in a year than faculty members. Finally, a faculty member may welcome a strength and conditioning coach who is willing to serve as a guest lecturer for a course. None of those examples should be limited to exercise science faculty as a strength and conditioning coach may have valuable contributions to make in courses within the psychology or business departments. In any of these cases, the point is to show the faculty member that the strength and conditioning coach, and their staff, do care about the student-athletes and should not be perceived as a negative influence on student-athletes. Those actions on the part of the strength and conditioning coach should be seen as investments of good will toward future collaborations or having an athletic-friendly faculty member on campus.

“For exercise science faculty, a concern may be that academic journal articles show that training and certification for strength and conditioning coaches does not necessarily lead to research-based training practices by strength and conditioning coaches.”

Tweet this quote

Administrators

One trait of a successful strength and conditioning coach is that of a hard work ethic (13). That work ethic often manifests itself as being willing to do certain tasks that no one else is willing or available to do, which often occurs beyond the awareness of administrators. Athletic directors are the leaders and managers of the athletic department. Part of their job is to have a vision and a resultant feeling of responsibility for the department as a whole, which seems likely to put them relatively far removed from so many of the tasks that strength and conditioning coaches execute on a weekly or daily basis. In practice, that means that a substantial portion of the strength and conditioning coach’s job description is not accounted for by administrators. Worse is that the administrator may then be under the impression that the strength and conditioning staff is available to take on more tasks. This is especially problematic when the head strength and conditioning coach wants to expand the amount of staff, change part-time roles to full-time roles, or add another graduate assistant position. When the administrator believes the strength and conditioning staff is already underworked, it is extremely difficult to justify adding more personnel to that staff. It seems unlikely that any good can come from administrators believing that the strength and conditioning staff is underworked and the responsibility for changing that perception falls directly on the strength and conditioning coaches, rather than the administrator.

There can sometimes be a chasm between perceived and actual time involved in being a strength and conditioning coach. This is simple and easy issue to address. Each strength and conditioning staff member should keep a log of all the activities they carried out while on the job. While this is a simple task, the execution of it may quickly become tiresome. However, if the problem with the administrators is a lack of awareness of what the job of strength and conditioning coach entails, this activity will solve that problem. There may also be benefits of keeping this log periodically for identifying potential areas for professional development, as well as being able to provide a more exact description of what being a head strength and conditioning coach looks like to novice coaches, interns, or when interviewing candidates to join the strength and conditioning staff. When it comes to anything professional development related, the initial starting point must be self-awareness (16).

Mentorship within strength and conditioning has received some attention in the literature (9,24,30). However, the assumption in these pieces is that a veteran strength and conditioning coach is mentoring a novice strength and conditioning coach. That is certainly of value to the novice coach and some veteran coaches have reported value as well (9). However, that keeps the knowledge within the strength and conditioning community, which likely does little for raising awareness of the strength and conditioning staff’s positive influences outside the strength and conditioning community (12). It may be wise for the head strength and conditioning coach to seek out mentorship relationships across campus to similarly positioned professionals. Establishing mutually beneficial mentorship-type relationships with department chairs, or similar positions, may prove advantageous. Essentially, the strength and conditioning coach should look for professionals who the athletic director is in meetings with outside of the athletic department. If an athletic director can hear positive reports about the strength and conditioning staff while at a non-athletic department meeting, it will reflect highly upon the strength and conditioning coach.

“When the administrator believes the strength and conditioning staff is already underworked, it is extremely difficult to justify adding more personnel to that staff.”

Tweet this quote

Community

It is also important to remember that faculty members, administrators, and other campus personnel are people that have neighbors, children in activities, and friends that are not associated with the school or organization. The importance of remembering this is that part of raising awareness of the strength and conditioning coach is making sure people are abreast of the good work accomplished in the training facility. The sport structure in the United States is such that most towns have sport systems outside of the school day for a variety of reasons (e.g., funding, facilities, time of year). For example, offering a strength and conditioning presentation to the director of the local soccer club, gymnastics facility, or swimming and diving club may be a way to connect with people not directly affiliated with the strength and conditioning coach’s employer. It is certainly reasonable that some of these opportunities lead to compensated follow-up work or additional training opportunities. Positively impacting athletes’ lives has been cited as a primary motivator for strength and conditioning coaches and finding more groups of people truly grateful for and willing to learn from the strength and conditioning coach can be fulfilling (27,33).

Specific to the youth sport context, sport coaches have reported being aware of sport psychology and yet being largely unaware of how it could benefit their coaching or their athletes (3). It is reasonable to conclude that the specific benefits of strength and conditioning may also be outside the knowledge base of youth sport coaches at the local soccer or gymnastics club, for example. Depending on the size of the institution employing the strength and conditioning coach, there may be an outreach department that specifically seeks to set up these sorts of campus-to-community collaborations. Investigating that possibility and investing in building these types of relationships could result in more campus allies for the strength and conditioning coach.

Developing Self-Efficacy as a Strength and Conditioning Coach

While there is little research of a direct nature on this problem of how to raise awareness of positive strength and conditioning coach, one area that might provide some guidance is that of coach self-efficacy. The research has typically been conducted with sport coaches, but there are some findings that are applicable to strength and conditioning coaches as well (23). All self-efficacy research traces back to Bandura’s model of self-efficacy, which posits there are four sources of self-efficacy: 1) mastery experiences, 2) vicarious experiences, 3) verbal persuasions, and 4) general affect (1). Most often, this has been applied to athletes for guidance on how to build their self-efficacy and self-confidence (7). However, it has also been noted that over-coaching can be a problem for some strength and conditioning coaches and one of the primary sources of over-coaching is a lack of confidence in coaching ability (15).

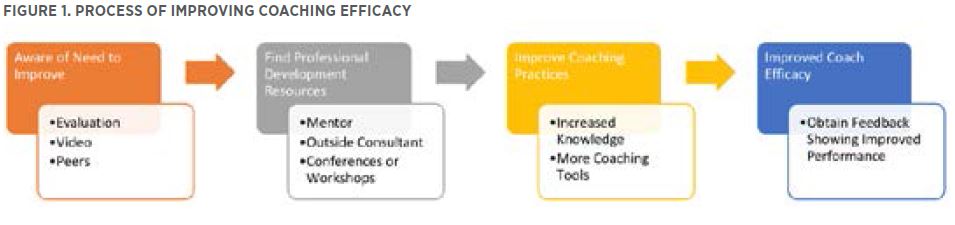

Figure 1. Process of Improving Coaching Efficacy

This lack of confidence is not surprising given the number of articles discussing how strength and conditioning coaches are undertrained on the soft skills (e.g., motivating athletes, communication) when they first enter the field (16,17,24,26). This leaves ample room for professional development opportunities; however, for a strength and conditioning coach to seek out those types of professional development activities, they first must be aware of the need (16). Figure 1 is an example of some of these steps. In order for mastery experiences to take place, the strength and conditioning coach must be cognizant of their weaknesses, seek out professional development resources to remedy the weakness, and actually remedy the weakness in coaching practice. That sequence is how the strength and conditioning coach will build self-efficacy through mastery experiences. This can be a daunting task for strength and conditioning coaches to undertake on their own. However, several solutions have been suggested, such as developing and instituting reflective practice and using video of coaching practices (4,21). The use of an outside coaching facilitator to guide the professional development has also been suggested (5). There are some articles discussing how difficult professional development for strength and conditioning coaches is given that the traditional recertification offerings may still be overly focused on the same educational components (e.g., program design) that were dominant in the strength and conditioning coach’s academic preparation (16). Ultimately, there are a variety of options for strength and conditioning coaches to improve their coaching efficacy, but those opportunities may require looking beyond the commonplace and having an open mind toward more novel approaches.

An alternative to the strength and conditioning coach having to move through all of those steps on their own is through the use of systematic coach evaluations. Unfortunately, coaching evaluation in strength and conditioning is rather haphazard (8). Strength and conditioning coaches have reported varying degrees of interest in coaching evaluation on the part of their direct supervisors (8). Additionally, strength and conditioning coaches may be unsure of their effectiveness and this can cause a host of problems.

If left to self-assess, strength and conditioning coaches are likely to suffer from self-serving bias; wherein, they will essentially give themselves the benefit of the doubt and may believe they are coaching at a higher level than is true (29). Any problems in the head strength and conditioning coach’s coaching practices or behaviors are likely to be passed along through the various levels of staff perpetuating the problems. That type of problem has been cautioned against in a variety of sport contexts (32,35). Without the objective feedback from the evaluation, mastery experiences are less likely as strength and conditioning coaches may simply not have any data to inform their perceptions regarding their coaching efficacy. In addition to the lack of mastery experience opportunities, the verbal persuasion piece may be absent or may consist only of the polite “good job,” without any substantive feedback or meaningful information.

Those same problems will also occur if the head strength and conditioning coach does not formally evaluate the entire strength and conditioning staff, which would provide opportunities for the junior staff members to improve in their coaching practices and then receive feedback on their progress toward improvement. More formalized evaluations may also help to identify some ineffective strength and conditioning coaches that could then be forced to either improve their coaching practices as part of continued employment or be removed from the field. One solution to this evaluation and administrators connection is to have more strength and conditioning coaches move into formal athletic administration roles (8).

“Establishing mutually beneficial mentorship-type relationships with department chairs, or similar positions, may prove advantageous.”

Tweet this quote

Conclusion

A final point across all these different groups is one related to the point in time that a non-strength and conditioning coach was first exposed to the field of strength and conditioning. At any point in the evolution, 10 years or 25 years ago, the strength and conditioning field then had less knowledge available and thus, less knowledgeable strength and conditioning coaches. In the early days, strength and conditioning coaches were biding their time waiting for a sport coaching job (14). It is important to remember that the administrator, or faculty member, that was first exposed to strength and conditioning 10 years ago may have been introduced to strength and conditioning by a coach that was already behind the times. Current research has shown gaps between best practices and what strength and conditioning coaches actually do in their coaching (18,19). There is every reason to believe that pattern has always existed with some strength and conditioning coaches who do not utilize the most current recommendations.

Similarly, it has been pointed out that it can be difficult for strength and conditioning coaches to keep up with all the new information in the field, which means it is wholly impossible to expect those outside the field to know as much as the strength and conditioning coach knows (19). Educating those around the strength and conditioning facility and staff may be the single easiest way to raise awareness of the strength and conditioning staff and the responsibility for delivering that education falls directly to the head strength and conditioning coach.

This article originally appeared in NSCA Coach, a quarterly publication for NSCA Members that provides valuable takeaways for every level of strength and conditioning coach. You can find scientifically based articles specific to a wide variety of your athletes’ needs with Nutrition, Programming, and Youth columns. Read more articles from NSCA Coach »

Related Reading

Traits of Successful Strength and Conditioning Coaches

Profile of a Strength and Conditioning Coach: Backgrounds, Duties, and Perceptions

Overcoaching in the Weight Room

A Model to Create Initial Experiential Learning Opportunities in Strength and Conditioning

The Disconnect between Research and Current Coaching Practices

A Review of Reflective Practice and its Application for the Football Strength and Conditioning Coach

References

1. Associate Press. Oregon strength coach suspended after players hospitalized. USA Today, January 18, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2018 from https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/ ncaaf/2017/01/17/oregon-strength-coach-suspended-after-playershospitalized/96701490/.

2. Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman, 1997.

3. Barker, S, and Winter, S. The practice of sport psychology: A youth coaches’ perspective. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 9(2): 379-392, 2014.

4. Carson, F. Utilizing video to facilitate reflective practice: Developing sports coaches. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 3(3): 381-390, 2008.

5. Culver, D, Trudel, P, and Werthner, P. A sport leader’s attempt to foster a coaches’ community of practice. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 4(3): 365-383, 2009.

6. Fortuna, M. Brian Kelly was trying to ‘control sideline’ in exchange with assistant. ESPN. November 1, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2018 from http://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/ id/14023721/notre-dame-fighting-irish-coach-brian-kelly-sayswas-trying-control-sideline-got-exchange-assistant-coach.

7. Gillham, A. Building better athletes through increased self-confidence. NSCA Coach 3(3): 16-18, 2016.

8. Gillham, A, Doscher, M, Fitzgerald, C, Bennett, S, Davis, A, and Banwarth, A. Strength and conditioning roundtable: Strength and conditioning coach evaluation. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 12(5): 635-646, 2017.

9. Gillham, A, Doscher, M, Schofield, G, Dalrymple, and Bird, S. Strength and conditioning roundtable: Working with novice coaches. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 10(5): 985-1000, 2015.

10. Gillham, A, Schofield, G, Doscher, M, Dalrymple, D, and Kenn, J. Developing and implementing a coaching philosophy: Guidance from award-winning strength and conditioning coaches. International Sport Coaching Journal 3(1): 54-64, 2016.

11. Gould, D. Conducting impactful coaching science research: The forgotten role of knowledge integration and dissemination. International Sport Coaching Journal 3(2): 197-203, 2016.

12. Grant, MA, Dorgo, S, and Griffin, M. Professional development in strength and conditioning coaching through informal mentorship: A practical pedagogical guide for practitioners. Strength and Conditioning Journal 36(1): 63-69, 2014.

13. Greener, T, Petersen, D, and Pinske, K. Traits of successful strength and conditioning coaches. Strength and Conditioning Journal 35(1): 90-93, 2013.

14. Hartshorn, MD, Read, PJ, Bishop, C, and Turner, AN. Profile of a strength and conditioning coach: Backgrounds, duties, and perceptions. Strength and Conditioning Journal 38(6): 89-94, 2016.

15. Janz, J. Overcoaching in the weight room. Strength and Conditioning Journal 31(2): 86-90, 2009.

16. Jeffreys, I. The five minds of the modern strength and conditioning coach: The challenges for professional development. Strength and Conditioning Journal 33(2): 43-45, 2011.

17. Jones, MT. A model to create initial experiential learning opportunities in strength and conditioning. Strength and Conditioning Journal 37(5): 40-46, 2015.

18. Judge, LW, Bellar, D, McAtee, G, Judge, M, Gilreath, E, and Connolly, H. U.S. collegiate hammer throwers: A descriptive analysis including the impact of coaching certification. Applied Research in Coaching Athletics Annual 27: 79-104, 2012.

19. Judge, LW, and Craig, B. The disconnect between research and current coaching practices. Strength and Conditioning Journal 36(1): 46-54, 2014.

20. Judge, L, Petersen, J, Bellar, D, Craig, B, Cottingham, M, and Gilreath, E. The current state of NCAA Division I collegiate strength facilities: Size, equipment, budget, staffing, and football status. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 28(8): 2253-2261, 2014.

21. Kuklick, CR, and Gearity, BT. A review of reflective practice and its application for the football strength and conditioning coach. Strength and Conditioning Journal 37(6): 43-51, 2015.

22. Lewinter, G, Weight, EA, Osborne, B, and Brunner, J. A polarizing issue: Faculty and staff perceptions of intercollegiate athletic academics, governance, and finance post-NCAA investigation. Journal of Applied Sport Management 5(4): 73-100, 2013.

23. Machida-Kosuga, M, Schaubroeck, JM, Gould, D, Ewing, M, and Feltz, DL. What influences collegiate coaches’ intentions to advance their leadership careers? The roles of leader self-efficacy and outcome expectancies. International Sport Coaching Journal 4(3): 265-278, 2017.

24. Magnusen, MJ, and Petersen, J. Apprenticeship and mentoring relationships in strength and conditioning: The importance of physical and cognitive skill development. Strength and Conditioning Journal 34(4): 67-72, 2012.

25. Massey, D. Program for effective teaching: A model to guide educational programs in strength and conditioning. Strength and Conditioning Journal 32(5): 79-85, 2010.

26. Massey, CD, and Maneval M. A call to improve educational program in strength and conditioning. Strength and Conditioning Journal 36(1): 23-27, 2014.

27. Massey, CD, Schwind, J, Andres, D, and Maneval, M. An analysis of the job of strength and conditioning coach for football at the Division II level. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 23(9): 2493-2499, 2009.

28. Mazerolle, SM, and Pitney, WA. How to address finding a balanced lifestyle in the athletic setting: A perspective for the strength and conditioning coach. Strength and Conditioning Journal 33(2): 43-45, 2011.

29. Miller, DT, and Ross, M. Self-serving biases in the attribution of causality: Fact or fiction? Psychological Bulletin 82(2): 213-225, 1975.

30. Murray, MA, Zakrajsek, RA, and Gearity, BT. Developing effective internships in strength and conditioning: A community of practice approach. Strength and Conditioning Journal 36(1): 35-40, 2014.

31. NSCA. NSCA strength and conditioning professional standards and guidelines. Strength and Conditioning Journal 39(6): 1-24, 2017.

32. Pim, RL. Values-based sport programs and their impact on team success: The competitive sport model at the United States Military Academy. International Sport Coaching Journal 3(3): 307-315, 2016.

33. Sartore-Baldwin, M. The professional experiences and work-related outcomes of male and female Division I strength and conditioning coaches. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 27(3): 831-838, 2013.

34. Tod, DA, Bond, KA, and Lavallee, D. Professional development themes in strength and conditioning coaches. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 26(3): 851-860, 2012.

35. Vallée, CN, and Bloom, GA. Four keys to building a championship culture. International Sport Coaching Journal 3(2): 170-177, 2016.

36. Wagner, K, Greener, T, and Petersen, D. Working with athletic trainers. Strength and Conditioning Journal 33(1): 53-55, 2011.

37. Watkins, J. Louisville’s strength and conditioning coach goes crazy on bench. Sporting News. February 6, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2018 from http://www.sportingnews.com/ncaa-basketball/news/ louisville-strength-conditioning-coach-ray-ganong-intense-basket ball/13rn0btz2s52l123elhh9veg7e

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

- Terms of Use

- Retraction and Correction Policy

- © 2026 National Strength and Conditioning Association