Six Essentials to Safe Participation

by NSCA's Essentials of Personal Training, Second Edition

Kinetic Select

May 2017

Hydration, footwear, and exercise frequency are only a few of the essentials to safe participation in cardiovascular activity. Make sure to include all six essentials in your program to ensure safe participation.

The following is an exclusive excerpt from the book NSCA’s Essentials of Personal Training, Second Edition, published by Human Kinetics. All text and images provided by Human Kinetics.

Safe Participation

The six variables that should be considered to ensure safe participation in cardiovascular activities are (1) proper hydration; (2) appropriate clothing and footwear; (3) warm-up and cool-down; (4) prescription of exercise frequency, intensity, and duration; (5) proper breathing techniques; and (6) exercise program variation. The following sections address these variables.

Hydration

Water makes up roughly 60% of the body mass and functions in regulating body temperature; acting as a solvent for glucose, minerals, amino acids, and vitamins; and provides a cushion and lubricant for joints. Thus, water is particularly important during high-intensity exercise in hot environments, when the body can lose as much as 2 to 4 quarts (about 2 to 3.8 L) of water every hour (30). The digestive system can absorb only approximately 1 quart (about 1 L) per hour. Thus, fluid replacement is most critical when high-intensity exercise is performed for an extended time period in a hot, humid environment.

Generally speaking, water is the best fluid replacement for exercise durations of less than 1 hour, but sport drinks with sodium and glucose are recommended for durations greater than 1 hour (27,30). In addition, although perspiration rates can vary widely among individuals and in different environments, approximately 5 to 7 ml of fluid per kilogram body weight should be consumed at least four hours prior to exercise. Furthermore, clients should be encouraged to weigh themselves before and after exercise and to replace each pound that is lost with 20 to 24 ounces (about 0.6 to 0.7 L) of fluid (28).

Clothing and Footwear

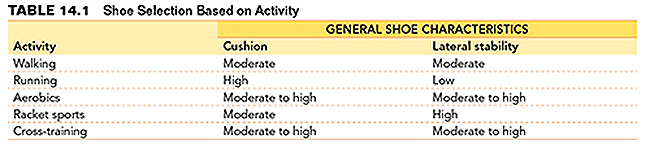

Comfortable, loose-fitting clothing is important during aerobic activities because it allows for ease of movement. In very hot environments, the clothing should be as light as possible, while layered clothing should be used in the cold. A great deal of the body’s heat is lost through the head and extremities in cold weather, so hats, gloves, and scarves are recommended to prevent excessive heat loss. Proper footwear is also very important for weight-bearing activities such as walking and running. Generally speaking, shoes should provide cushioning, stability, and comfort while maintaining flexibility.

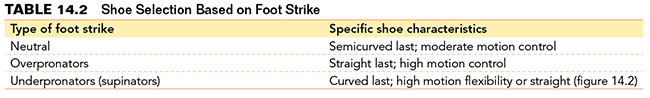

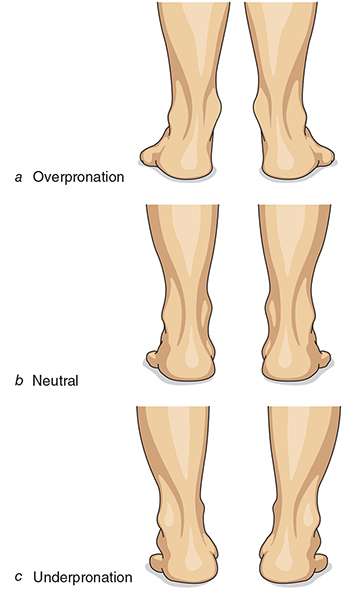

The primary factor determining the quality of a running shoe is its compression capabilities, 50% of which are lost within 300 to 500 miles (483 to 805 km) of use (15). Of course, some running shoes are better than others; but in general, most running shoes should be replaced after 300 to 500 miles of use or every six months, whichever comes first. Runners with a high body weight or an unusual gait (e.g., overpronation or underpronation) may require more frequent shoe replacement. Tables 1 and 2 provide recommendations for shoe selection based on the type of activity and foot strike characteristics, and Figure 1 provides an illustration of overpronation and underpronation.

Running shoes are generally made with three different types of forms: straight, semicurved, or curved (figure 14.2). Overpronators may benefit from a motion-control shoe with a straight last. Underpronators may favor a shoe with a curved last that allows greater foot range of motion. Neutral foot strikers may benefit from shoes with a semicurved last and moderate direction- and foot-control features (14). A consultation with a podiatrist to analyze running biomechanics may be helpful for proper shoe selection.

Figure 1: (a) Overpronation occurs when the foot collapses too far inward on the arch with each foot strike. (b) Neutral foot strike. (c) Underpronation (supination) occurs when foot strikes are too much on the outsides of the feet and have too little inward roll.

Figure 2: The shapes of straight, semicurved, and curved lasts. Overpronators may benefit from straight lasts, neutral foot strikers from semicurved lasts, and underpronators (supinators) from curved lasts.

Warm-Up and Cool-Down

Warm-up and cool-down activities help the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems adjust to the workload used during the exercise. If the training program requires exercise at a target heart rate, a 5- to 15-minute warm-up should be used to gradually increase heart rate to the target level, and the exercise session should be followed by a 5- to 15-minute cool-down to reduce heart rate. If desired, 5 to 15 minutes of low-intensity stretching exercises can also be used to help loosen up stiff muscles and joints after the warm-up or as part of the cool-down (see chapter 12).

Exercise Frequency, Intensity, and Duration

The following are general guidelines for frequency, intensity, and duration of cardiovascular exercise (2).

• Frequency: 2 to 5 sessions per week

• Intensity: 50% to 85% of heart rate reserve

• Duration: 20 to 60 minutes

Generally speaking, most clients are capable of performing a single exercise session continuously. Deconditioned clients, however, may benefit from intermittent bouts performed throughout the day. Chapter 16 provides information on designing aerobic endurance training programs.

Proper Breathing Techniques

It is important for clients to understand that it is not necessary to exercise in a state of breathlessness to achieve cardiovascular benefits. In general, breathing during cardiovascular exercise should be relaxed and regular. A general recommendation is that clients should be able to carry on a casual conversation while exercising and breathing through both the nose and mouth. However, competitive clients may require more advanced training techniques, such as sprint or interval training, that elicit high heart and breathing rates.

Exercise Program Variation

Exercise program variation is important for reducing the chances of overuse injuries. It is also important to remember, however, that introducing new exercises into a program will usually require decreases in intensity. For example, a client who has been riding a stationary bike for 30 minutes three times per week may not be able to immediately switch to treadmill running for 30 minutes three times per week. Instead, the client should be gradually acclimated to the new activity.

In addition, each exercise presents a unique stress, thereby eliciting adaptations that are specific to that modality. General adaptations to the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems carry over well from one exercise to the next, but the client’s musculoskeletal system and connective tissues will not be accustomed to the mechanical stresses of running if she is usually cycling. Thus, personal trainers should pay careful attention to their clients as they adapt from one exercise modality to the next.

This article originally appeared in Personal Training Quarterly (PTQ)—a quarterly publication for NSCA Members designed specifically for the personal trainer. Discover easy-to-read, research-based articles that take your training knowledge further with Nutrition, Programming, and Personal Business Development columns in each quarterly, electronic issue. Read more articles from PTQ »

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

- Terms of Use

- Retraction and Correction Policy

- © 2026 National Strength and Conditioning Association