Energy System Training

by NSCA's Essentials of Tactical Strength and Conditioning

Kinetic Select

April 2022

This excerpt from NSCA's Essentials of Tactical Strength and Conditioning aims to educate on some fundamentals of energy systems training in tactical personnel.

The following is an exclusive excerpt from the book NSCA's Essentials of Tactical Strength and Conditioning, published by Human Kinetics. All text and images provided by Human Kinetics.

Although aerobic fitness has a place in the training of police officers, it does not supply the bulk of the immediate energy supply at critical times when officers have to protect themselves or others from injury. Such critical times usually range from 15 to 20 seconds to less than 2 minutes (88).

To increase the specificity of training, methods involving the anaerobic energy system, such as interval training, should be used instead of LSD running. Interval training consists of high-intensity work followed by a low-intensity recovery or rest. This training works both the anaerobic and aerobic energy systems, integrating the energy systems in differing amounts—similar to what may occur in real life—rather than attempting to use each energy system in isolation (35).

Interval training improves the ability of the muscular system to resist fatigue by exposing it repeatedly to bouts of high-intensity exercise (54). Interval training has also been shown to result in greater improvements in running speed than long-distance running alone, especially in sedentary and recreationally active people (58).

Having the ability to resist fatigue during high-intensity activities would assist police officers with many of their critical tasks, such as crowd control, physical restraint, and self-defense. As officers are able to produce the required effort for a longer time, they increase their ability to recover more efficiently after performing the task. Anaerobic training through high-intensity intervals, strength training, plyometrics, and agility training can elicit specific adaptations in the nervous system. These adaptations lead to greater muscle fiber recruitment, rate of motor unit firing, muscle synchronization, and muscle function, resulting in increased strength and power.

Some of the chronic responses to excessive aerobic endurance training decrease muscle mass, strength, speed, and power, which may increase the number of injuries suffered by police officers. To prevent this from happening, the program should focus on interval running based on the termination velocity of the 30-15 intermittent fitness test (30-15 IFT) (25). The 30-15 IFT consists of 30-second shuttle runs for 40 m (44 yd) interspersed with 15-second passive recovery periods. The test commences at a velocity of 8 km/h (5 mph) for the first 30-second run and increases by 0.5 km/h (0.3 mi) every 45 seconds thereafter. This continues until the participant can no longer complete the test (24).

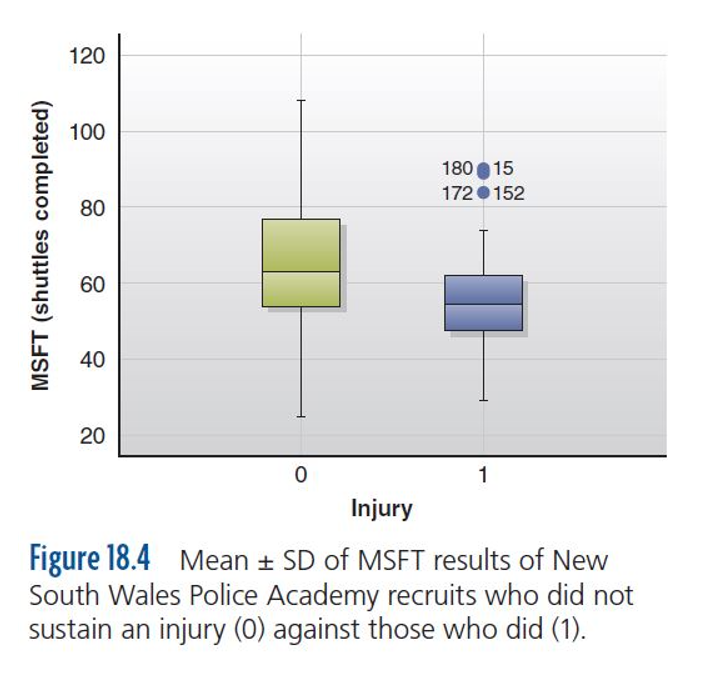

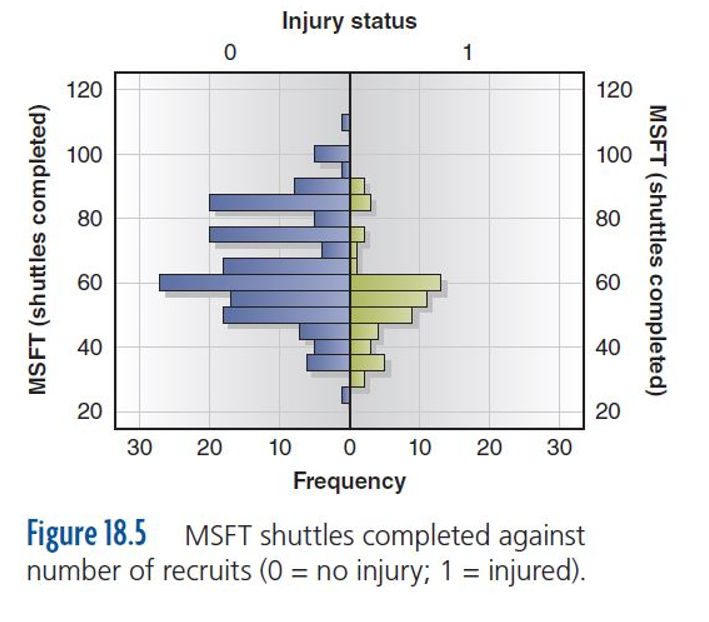

Research has shown that recruits who start an academy training program with a lower level of anaerobic and aerobic fitness have a higher chance of sustaining an injury during training (80), as shown in figure 18.4. The recruits who sustained an injury (group 1) during training ran an average of 10 fewer shuttles on the Multi-Stage Fitness Test (MSFT) than those who did not sustain an injury (group 0). Figure 18.5 shows the dispersion of those recruits who sustained injuries compared with those who were not injured. Whereas 83% of participants who did not perform more than 33 shuttles were injured, only 39% of participants who performed a minimum of 52 shuttles were injured. At the level of 53 shuttles (level 6.1 or 1,040 m [1,137 yd]), the MSFT was able to predict 97.5% of injuries with a false negative rate (i.e., officers who were predicted to suffer an injury but did not) of 2.5%.

The problem TSAC Facilitators face is how to improve the energy systems without increasing the risk of injury. Increasing VO2 in large tactical groups has previously been achieved using longer distance intervals or continuous running (80). These programs are generally one size fits all, aiming at either the average recruit or the lowest common denominator. This can lead to overtraining or undertraining a large portion of the group, as well as increasing the rate of injuries.

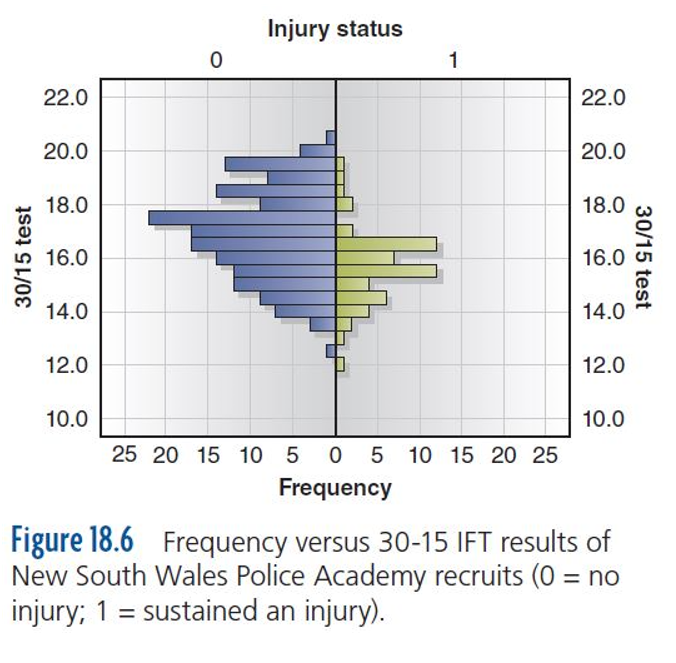

A solution to this problem is to implement individualized running programs or ability-based training (80). As an example, the 30-15 IFT (figure 18.6) is a prescription test that allows individual running programs to be implemented based on termination velocity (23).

At the conclusion of the 30-15 IFT, the recruit’s termination velocity is expressed as kilometers per hour. This number is divided by 3.6 to provide a figure that is expressed as meters per second (m/s). This number is then entered into a spreadsheet where running intervals are derived from the following formula (80):

Interval distance = running speed in m/s × % of effort × duration of interval

Ability-based training programs have been shown to reduce the incidence of injury and improve VO2 measures when compared to longer intervals and continuous running or control groups (80). When undertaken in the initial phase of training, there was no difference in ability-based training compared to a standardized running program. During this phase, the recruits participated mainly in classroom activities and theory lessons. In phase 2 of training, however, the focus shifted from the classroom to defensive tactics and scenario-based training. In the final physical test, the recruits who completed the ability-based training outperformed the recruits who completed the standardized running programs. This may be due to the added volume and time spent on the standardized program that increased the total training load in comparison to ability-based training (80).

NSCA's Essentials of Tactical Strength and Conditioning is the ideal preparatory guide for those seeking the Tactical Strength and Conditioning Facilitator® (TSAC-F®) certification, and a reference for fitness professionals who work with tactical populations such as military, law enforcement, and fire and rescue personnel. The book is available in bookstores everywhere, as well as online at the NSCA Store.

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

- Terms of Use

- Retraction and Correction Policy

- © 2026 National Strength and Conditioning Association