Elastic Bands – Resisted and Assisted?

by Developing Power

Kinetic Select

August 2023

This excerpt from Developing Power explains how to use bands for variable resistance training.

The following is an exclusive excerpt from the book Developing Power, published by Human Kinetics. All text and images provided by Human Kinetics.

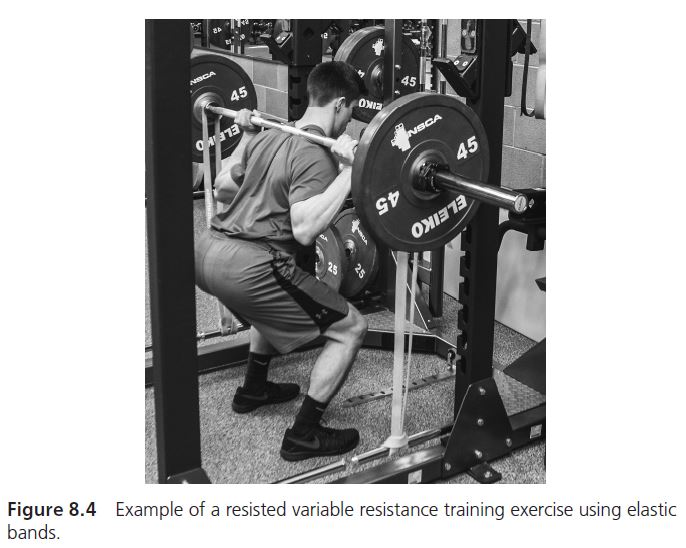

When performing VRT using elastic bands, coaches and athletes have their choice of methods. The way in which they set up the exercise directly affects the potential to express maximal power output. Used in association with free weights, elastic bands can either resist or assist a given movement pattern. When using elastic resistance, wrap rubber banding around the ends of a barbell and then anchor it to the floor with a heavy weight or the base of a power rack. The force vectors should allow vertical resistance to the floor (61). In such a setup, exercises like the squat, the shoulder press, and the bench press experience the least resistance at the lowest point of bar displacement where there is a mechanical disadvantage. This mitigates the potential effect of sticking points, and allows the bar to be accelerated at a faster rate. With ascending displacement of the bar, the elastic bands stretch and the tension progressively increases; the mechanically strong portion of the exercise is then associated with progressive recruitment of higher-order motor units and a resulting higher Ppeak (49, 70). The setup for resisted VRT is shown in figure 8.4.

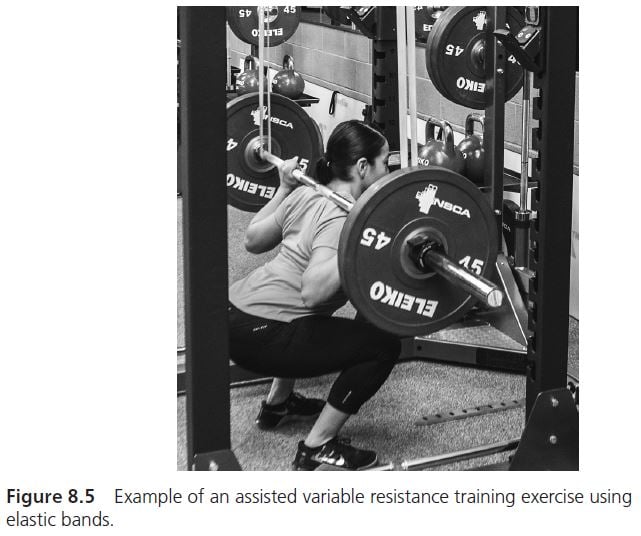

In comparison to resisted VRT, assisted training methods are set up with the resistance reversed. In assisted training, the viscoelastic properties of the rubber bands augment the ascent of a bar against gravity. By anchoring the bands at a height (figure 8.5) during bar descent in exercises, such as heavy back squats, the elastic will stretch, reducing the total load at the bottom of the squat. The bands promote rapid movement out of the bottom position. As the athlete rises to return to standing, the magnitude of assistance is reduced throughout the ascent, and the musculature must once again take on more of the force-generating requirements within mechanically advantageous ranges. Assisted VRT methods have been shown to result in greater power and velocity output, with increased shortening rate and neuromuscular system activation reported as potential underlying mechanisms (67, 68, 91).

Programming the use of VRT techniques requires an understanding of the impact that exercise setup has on the nature of the physiological stimulus imposed. When used in a resistive fashion, research suggests that elastic bands both complement the length–tension relationship and promote the progressive recruitment of high-order motor units. Indeed, improvements in RFD have been shown after training with resistive elastic band setups (68, 86, 103). Longer peak-velocity phases, an exploitation of the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC), and an increase in elastic stored energy all were reported. In comparison, assisted VRT exercises may be more desirable during periods of heavy competition, when athlete loads may be compromised by higher levels of fatigue, or during an overspeed training phase, where the speed of movement is the primary training objective (106). Assisting a movement task with the addition of elastic bands allows athletes to explode out of the bottom position of movements, such as the squat or bench press, which in turn increases task specificity, promotes high power outputs, and translates to many ballistic movements found in sport performance, such as jumping and throwing (68, 86). Examples of exercises using bands are outlined in chapters 5 and 6.

With Developing Power, the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) has created the definitive resource for developing athletic power. With exercises and drills, assessments, analysis, and programming, this book will elevate power and performance in all sports. The book is available in bookstores everywhere, as well as online at the NSCA Store.

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

- Terms of Use

- Retraction and Correction Policy

- © 2026 National Strength and Conditioning Association